In Japan, Takaichi’s Election is a Political Milestone. But Women Remain Divided on What’s Next.

TOKYO — When Sanae Takaichi was elected as Japan’s 104th prime minister in October, the career politician and Nara native made history as the country’s first-ever female leader. Yet three months into her tenure, reactions among Japanese women are far from uniformly celebratory.

Takaichi’s administration includes only two women ministers, Finance Minister Satsuki Katayama and Economic Security Minister Kimi Onoda, compared with as many as five women in some earlier cabinets, including that of former Prime Minister Fumio Kishida. Some of her early policy priorities are already wringing hands: For one, her platform emphasizes a return to traditional family roles and a relentless, virally quoted “work, work, work, and work” ethic, suggesting that symbolic progress on gender equality may mask the systemic setbacks faced by Japanese women.

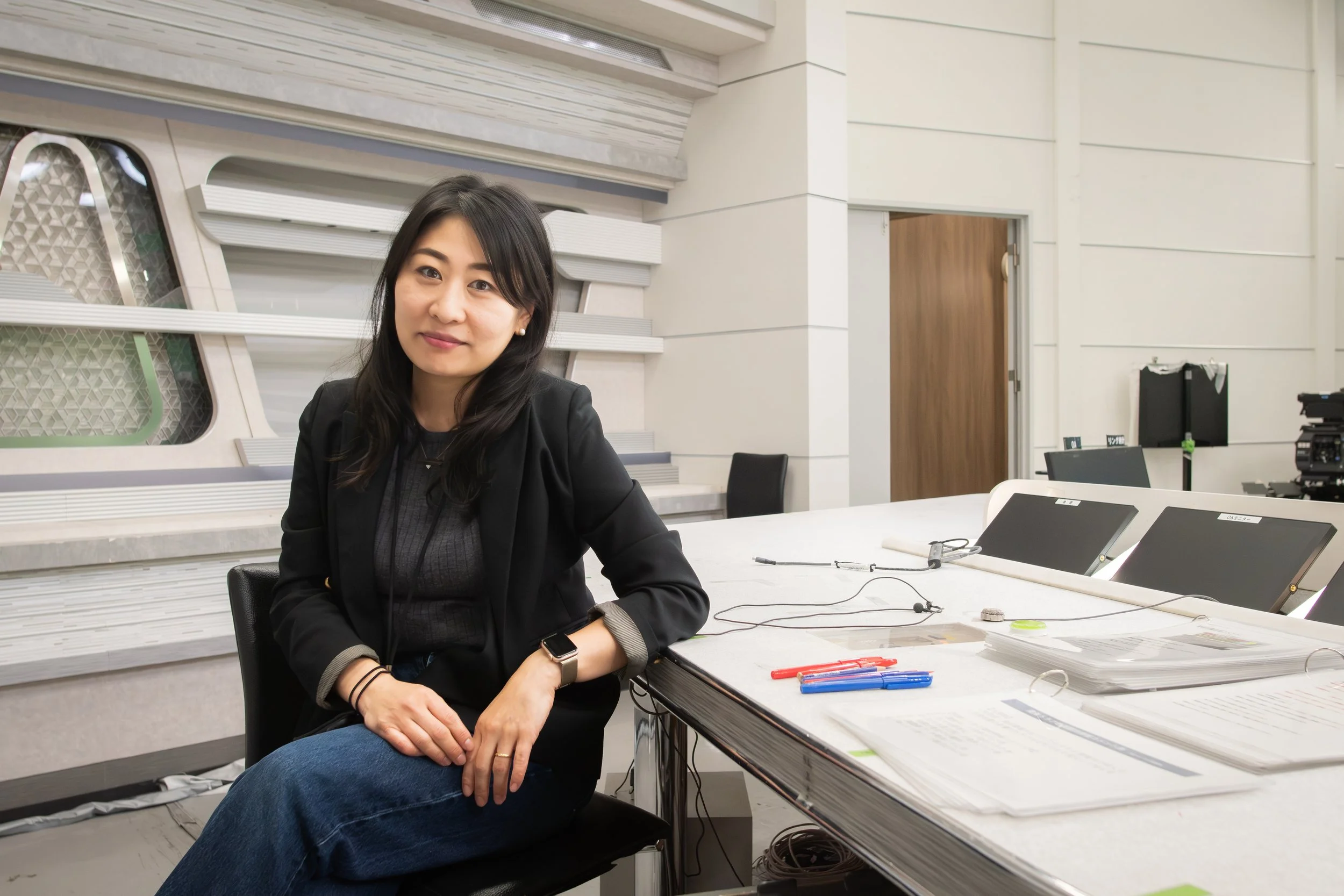

For Yuka Mizoue, a Tokyo-based journalist for TV Asahi and founder of the newly-formed Japan Women Journalists Association, Takaichi’s appointment brings forth a new era of possibility — and frustration.

Yuka Mizoue at TV Asahi headquarters in Tokyo on Nov. 26, 2025. Mizoue has reported on working women, caregiving and gender equality in Japan for nearly 20 years. Kelly Kimball for More to Her Story.

Before becoming a mom in 2011, Mizoue spent several years at TV Asahi, including as an assistant director and then director on the evening news. After her daughter was born, she was steeped in Japan’s historic shortage of licensed childcare facilities, forcing her to look for more costly, unlicensed alternatives. “All the money I earned was mostly going into my childcare,” she said.

After returning to work, she found herself cut off from challenging assignments and pushed into repetitive tasks like daily audio transcription, which made her realize how systemic barriers limited women’s professional advancement. “It really got on my nerves, because I couldn't do the job that I really wanted to do,” she said.

It inspired her to build inroads in her newsroom to report on the very indignations with childcare she experienced. “But to cover that story, I had to negotiate with producers and other cameramen, to make them understand that this was the story we needed to air. That process was really hard,” she recalled. Once the story aired, however, it sparked widespread attention, with other media outlets following her coverage.

“I felt that I made change in the society, but in the newsroom, nobody recognized that my news made things happen,” she said. “That was the first experience for me… covering gender issues in this newsroom was pretty hard.”

Mizoue is cautious in her commentary on Takaichi. “It’s hard to criticize Takaichi because she has very high approval ratings,” she explained. (An NHK opinion poll released earlier this month found that approval of Takaichi's cabinet dropped two percentage points from the previous month, but still stands high, at 64 percent.) “There’s a sense that if women journalists speak too strongly, the male-dominated media will turn on us.”

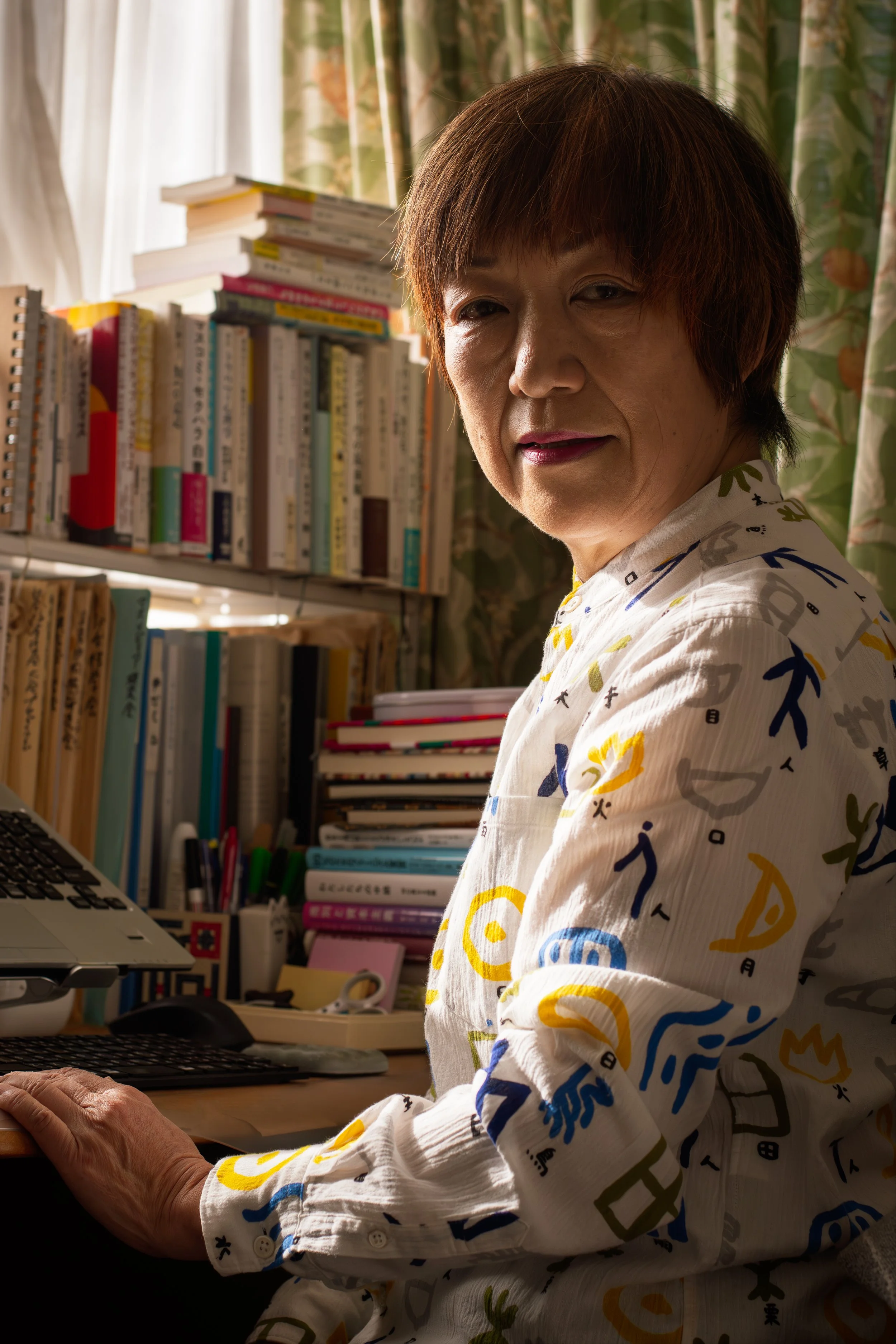

Some women in advocacy and academia remain skeptical about Japan’s progress on gender equality. Yoshiko Hayashi, a former Asahi Shimbun journalist and a doctoral student at Ochanomizu University who studies sexual harassment of women journalists, points to deep-rooted structural barriers. Japan ranked 118th out of 148 countries in the World Economic Forum’s 2025 Global Gender Gap Report released in June — last among G7 nations. Hayashi attributes the low ranking to entrenched patriarchy, conservative social norms and cultural pressures that discourage women from speaking out.

Pictured: Yoshiko Hayashi in her home in Tokyo, Japan, on Nov. 26, 2025. Kelly Kimball for More to Her Story

“People do not demonstrate or express their thoughts because it is considered ‘meiwaku’ — causing inconvenience to others,” Hayashi said, describing a widespread reluctance to publicly voice dissent. “I am afraid that under Takaichi, Japanese feminism might not go forward; it might even go backward.”

Despite recent reforms, progress remains uneven. Since 2022, private companies with more than 300 employees have been required to disclose their gender pay gap annually. Yet women continue to earn a striking 22 to 25 percent less than men and still hold just 16 percent of leadership roles in Japan, compared with about 40 percent in the United States, and according to a new report by the World Economic Forum.

Those concerns reflect broader institutional resistance. In January, Japan withdrew funding from the U.N. Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women after the body urged reforms to Japan’s male-only imperial succession law, a move critics saw as signaling reluctance to accept binding international gender-rights standards. Legal and cultural constraints also continue to shape expectations around women’s roles in work, leadership, and family life, including Japan’s status as the only developed country that requires married couples to share a surname, a policy Takaichi supports.

Pictured: Hayashi worked with a team at Ochanomizu University to translate the book Reproductive Justice: An Introduction, noting there was no direct, single-word Japanese translation for the term "reproductive justice."

“Many people, mostly men, say feminists should be satisfied just because Japan may have its first woman prime minister,” said Hayashi. “But behind those comments, I feel a kind of oppression.”

Kumico Nemoto, a professor at Senshu University and a scholar of gender inequality, said Takaichi’s political career has long reflected traditional views of women and families.

Under former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s push to increase the number of women employed and in leadership roles, the number of employed women soared, but the increase in women leaders in industry and politics remains slow, explained Nemoto, emphasizing that Takaichi could continue a similar approach. “But she hasn’t addressed anything regarding women’s employment or leadership. She hasn’t even clarified her broad vision regarding Japan’s population decline, worsening labor shortage, and increasing reliance on foreign workers, and diversity policies, as well as gender equality, which are all crucial to make Japan strong,” she said in an email to More to Her Story.

Nemoto added that these omissions stand in contrast to Takaichi’s emphasis on expanding military spending, a priority she recently underscored in talks with U.S. President Donald Trump in October.

Mari Hamada, founder of the advocacy group Stand By Women, in front of the gates of Ochanomizu University in Tokyo, Japan, on November 26, 2025. Kelly Kimball for More to Her Story.

Mari Hamada, founder of the advocacy group Stand By Women, also warns against overestimating the impact of symbolic milestones. Her organization, established in 2021, provides advice, training and research to help Japanese female political candidates navigate online abuse and workplace harassment.

“Harassment is still very prevalent for women in politics,” Hamada said. “Many people don’t believe it happens because politicians are seen as powerful. But our research shows that increasing the number of women in office is linked to fewer harassment incidents.”

Her team has met with hundreds of politicians and staffers across Japan, holding training sessions meant to spark change and build awareness. But public discussion remains rare, and for many women, the stigma around speaking out still feels heavier than the promise of being heard. “Coming forward about harassment is often seen as showing weakness,” Hamada said. “There isn’t a space for women politicians to talk about these issues yet. That’s what we are trying to create.”

This lack of open discussion of harassment is reinforced by women’s severe underrepresentation in Japanese politics: A June 2024 report placed Japan 160th out of 186 countries for the share of women in the House of Representatives, and 165th worldwide overall. Despite women making up more than half of Japan’s electorate, the country ranks near the bottom globally for female political representation. Surveys and reporting by Asahi Shimbun and The Guardian found that many female politicians face sexist language, online abuse, and gender-based insults, yet often feel pressure to endure it quietly rather than speak out. Hamada explained harassment in Japan is often treated as an individual burden rather than a structural problem.

Women in the publishing industry gather to celebrate the launch of the translated version of the book Financial Feminist by Tori Dunlap, which became a New York Times bestseller in 2022, at Kanki Publishing's headquarters in Tokyo, on Nov. 26, 2025. Kelly Kimball for More to Her Story.

“[Takaichi’s] victory shows that a hardworking woman from a middle-class family, not a political dynasty, can become prime minister,” said Nemoto of Senshu University. “But her conservative values, if enacted, may alienate younger generations and women seeking equality in the workplace and society.”

That uncertainty has only sharpened in recent weeks. During the latest Diet, or parliament, session that closed on Dec. 17, Takaichi signaled priorities that unsettled many observers.

“In addition to expanding defense spending, she has raised the idea of relaxing limits on overtime,” Nemoto said in an interview with More to Her Story in November, during the Diet session. “Whether she expects Japanese people to work longer hours is unclear, but these moves remind many of the slogan to ‘enrich the country and strengthen the military’ under imperial Japan.”

For women already navigating the challenging bind of long work hours, limited leadership opportunities and widening inequality, Nemoto said the silence on gender policy is as telling as the proposals that have surfaced.

“She has a huge responsibility in this, and she could have many women on her side, but so far, she seems to be busy exercising her power in other areas,” said Nemoto.

As Takaichi moves from history-making symbolism to governing reality, the question many women are asking is no longer whether Japan can elect a woman prime minister — but whether her leadership will make space for women to move forward with her.