After Roe, Churches Promised to Support Women. Three Years Later, Has Anything Changed?

In the summer of 2022, a development long anticipated by many American Christians sent shockwaves across the nation: Roe v. Wade was overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Reactions rippled across the country, ranging from horror to perplexity to celebration. For many who rejoiced, the ruling felt like the fulfillment of a promise years in the making. They had cast their votes for U.S. President Donald Trump, whose three Supreme Court appointments — Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett — reshaped the Court and made such an outcome possible. Yet while some voters had indeed hoped for this moment, surveys offer no clear measure of how many supported Trump with the explicit expectation that Roe would fall.

Scholars and analysts suggest that, for most, the choice was rooted less in a single issue than in a broader constellation of conservative and religious convictions about faith, morality, and the sanctity of life.

“More than ever, those who value all human life must demonstrate their commitment not merely with their words, but also by their deeds,” said Adam Greenway, then president of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, in a June 2022 statement following the Supreme Court’s Dobbs abortion decision: “We must urge legislators to protect the unborn, and we must provide compassionate support for women that will help them choose life.”

His call to action became a fervent rallying cry for Christians, particularly across the American South where abortion would become more heavily restricted in a cascade of state-level policies enacted over the next few years, to defend their belief in the sanctity of life without neglecting the well-being of mothers.

With fresh urgency, many demanded that the Church take concrete action to support women. But three years later, have those calls translated into real impact?

For many women, making the complex and personal choice to have a child predated the overturning of Roe v Wade.

In the late 1990s, nineteen-year-old Amy Ford sat on the exam table at a Planned Parenthood clinic in Fort Worth, Texas. She had grown up in a devout Christian household where she was taught, and sincerely believed, that sex was reserved for marriage and that every unborn life held value. Yet now, pregnant and unmarried, her beliefs collided with her reality. Fear pressed in from every side: fear of her parents’ disappointment, of judgment from her church, and of the limits a baby might place on the future she had imagined for herself. Desperate for a way out, she determined there was no other choice but to end the pregnancy.

Amy Ford with her newborn baby, Jess, in 1998, image provided by Amy Ford

As she waited for the procedure to begin, her racing thoughts became too much and she fainted. When she came to, the nurse suggested she take more time to think before moving forward. Still shaken, Amy left the clinic to speak with her boyfriend. In the days that followed, through many long conversations, they made the difficult decision to continue the pregnancy and to marry, ready to face whatever came next together.

That complex decision, Ford soon realized, would not be the most difficult part of their journey. When they asked their pastor to officiate the wedding, he refused, emphasizing that a child conceived out of wedlock was shameful and he could not bless their marriage.

“We found someone else who would marry us, but it definitely felt like a scarlet letter experience,” Ford said. “We felt shame on our wedding day. Then we tried to go back to church, but there was an elephant in the room and people didn’t know whether they should say ‘congratulations’ or ‘I’m sorry’, so they just didn’t say anything. We felt alone in a crowd of people.”

Amy Ford and her husband Ryan on their wedding day in 1998, image provided by Amy Ford

Although Ford’s story unfolded 25 years ago, the paradoxical landscape that shames single motherhood yet discourages abortion still exists, said Ford, forcing many women to weigh impossible options: If they keep the baby, they risk becoming a pariah within their congregation; if they end the pregnancy, they risk exile from the very community that could have supported them.

Research through the years paints an even clearer picture: According to a May 2015 survey conducted nationally by the evangelical research firm Lifeway Research, 64 percent of women who have had an abortion say church members judge single women who are pregnant and are more likely to gossip about a woman considering abortion than help her understand her options.

In 2021, the year before the overturning of Roe v. Wade, Lifeway conducted another national survey, asking Christian Americans this question:, “If Roe v. Wade was overturned, would religious organizations in your state have a responsibility to increase support or options for women who have unwanted pregnancies?” 74 percent said yes. When asked whether the state should also be obligated to do more, a majority also agreed.

By 2024, Lifeway revisited these questions, asking Christians if their churches were taking action. The largest share, 44 percent, said they had not heard anything from their church about supporting women facing unplanned pregnancies, and 16 percent said they were unsure. Only 31 percent reported that their church was encouraging congregants to financially support and offer volunteer help to local pregnancy resource centers.

“Communities across the country, specifically evangelical Christian groups, are the primary source of volunteer help as well as financial help for pregnancy resource centers,” said Scott McConnell, executive director at Lifeway. “The expectation from all Americans is that people of faith, as well as our government, would step up to help women in a bigger way in states where abortion is restricted. It’s still yet to be seen whether Christians have been willing to increase their support to the sacrificial level that it would take to meet that greater need,” said McConnell.

Historic Presbyterian church at sunset in Norcross, Georgia, credit: Olivia Bowdoin for More to Her Story

But even if churches dramatically increased their support of these pregnancy centers, the effectiveness of PRCs remains uncertain, researchers warn.

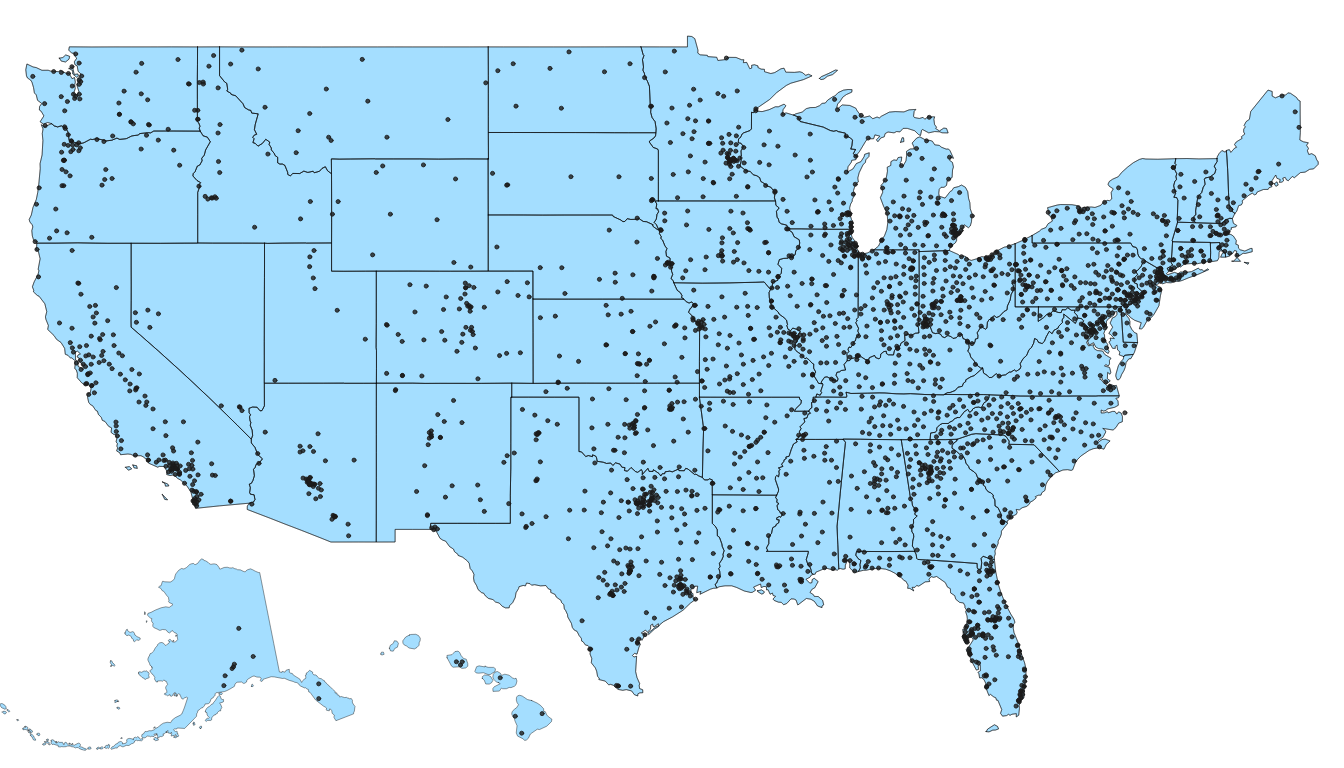

Map of Pregnancy Resource Centers as of March 31, 2024. Credit: crisispregnancycentermap.com

Pregnancy resource centers have a long history in the fabric of American reproductive conversations, originating in the 1960s and 1970s as grassroots, often faith-based organizations offering free counsel and material support to pregnant women all over the country. Most are located in the Southeast, a region colloquially referred to as the Bible Belt.

Over time, many centers expanded their services to include parenting classes, adoption guidance, and referrals for healthcare, while increasingly emphasizing efforts to dissuade women from choosing abortion.

Dr. Katrina Kimport, a qualitative medical sociologist whose research focuses on gender, health, and reproduction, has spent decades researching who visits PRCs and why. She found that while PRCs often aim to dissuade abortion, most visitors have already chosen to continue their pregnancies and are seeking material or emotional support.

“This idea of intendedness and planning is in many ways not available or interesting to huge portions of people with reproductive abilities. That’s not how most people create their families,” Kimport explained. Nearly half of all U.S. pregnancies are unintended, yet 60 percent are carried to term, according to the Guttmacher Institute — numbers that, as Kimport notes, complicate the assumption that “unintended” equals unwanted or harmful.

“This idea of supporting women experiencing unintended pregnancies… that this would somehow be a more acute need following Dobbs doesn’t really hold water,” she said, noting that the free services and material goods PRCs are providing are appreciated by clients, but not enough.

Kimport called PRCs a “privatized and evangelically, religiously informed response to a very frayed social safety net — a well-meaning effort that fails to address the systemic problems shaping women’s reproductive choices.”

“There are still substantial needs,” she said.

Research consistently shows that reproductive decisions, including whether to terminate a pregnancy, are closely tied to systemic socioeconomic factors. According to another Guttmacher Institute study, 41 percent of women seeking abortions had incomes below the federal poverty level in 2021. An additional 30 percent had incomes just above it, meaning roughly seven in ten people obtaining abortions live at or near the poverty line. Both the study and Kimbort confirm that higher abortion rates are linked to inadequate access to the resources that support pregnancy and child-rearing, including affordable healthcare, safe housing, and quality childcare.

Further, maternal mortality is disproportionately concentrated among low-income communities and black and indigenous populations, underscoring the health risks that shape reproductive decision-making, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Studies indicate that expanding access to comprehensive healthcare, living wages, subsidized childcare, and affordable housing can reduce these pressures and give women greater agency to carry pregnancies to term if they choose. Abortion decisions, these findings make clear, are embedded within structural inequities that constrain options for people with limited resources.

Yet a woman’s choice about her pregnancy is still more than a matter of law or material need; it is profoundly cultural and spiritual.

Britani Anthony photographed by Olivia Bowdoin for More to Her Story

In Atlanta, Britani Anthony is one of the few within her community asking what role faith communities should play in closing the persistent gap between society safety nets and persistent inequities. A black woman, Christian advocate, and leader with the AND Campaign’s Whole Life Project, she works to change the narrative around abortion. The group’s goal is to “protect unborn life while valuing the life of the mother,” addressing issues such as maternal mortality, poverty wages, and access to healthcare and quality childcare. Anthony speaks openly about balancing these dual priorities, and her approach to advocacy has evolved over time.

Active in politics as a teenager, Anthony once imagined herself following in the footsteps of Cecile Richards, the former president of Planned Parenthood. But after befriending members of the Christian campus ministry Chi Alpha, she began wrestling with complex questions, wondering whether, if life was created by God, it might also deserve protection. Her faith deepened, and she joined the pro-life movement, volunteering in what she calls “sidewalk ministry,” where she and others would wait outside abortion clinics to talk with women about alternatives to abortion. The experience proved formative to her current work.

“Because sidewalk ministry is mostly dominated by conservative white evangelicals, there are a lot of issues that are difficult to talk to them about,” said Anthony. “If you’re ministering to mostly black and brown women who are going to get abortions, unless you acknowledge that there are still racial issues that are systemic and need to be addressed, there is going to be tension.”

Anthony came to question the narrow view shared among many “sidewalk ministry” volunteers that the most important part of the abortion conversation is simply convincing women not to have one. She mused that many Christians might misguidedly fear nuance because it may require compromising their convictions. Instead, she professes that nuance means being brave enough to ask: What might be going on behind the scenes that I’m not seeing? How can I put myself in another person’s shoes?

Today, her work invites others to look beyond simple explanations for abortion rates in the United States. She points to factors such as sexual violence, persistent racial inequities, the isolation of motherhood, and the challenges many face accessing affordable healthcare, childcare, and housing. For Anthony, understanding these realities is essential to creating genuine and lasting support for women.

Dr. Andrea Swartzendruber, a public health researcher at the University of Georgia, said faith-based pregnancy support systems, such as “sidewalk ministry” and PRCs, are often portrayed as the only viable solution to the systemic challenges faced by women debating their pregnancy — but there are limits to what they can do, and have done. The underlying assumption at many well-meaning faith-based organizations, Swartzendruber said, is that all women need is encouragement. But she emphasized that structural, medical, and emotional needs extend far beyond reassurance and cheerleading.

Pregnancy resource centers often disseminate misleading health information. A 2020 study published in Women’s Health Reports examined 254 websites representing 348 faith-based pregnancy resource centers and found that 80 percent contained at least one false or misleading claim. Some centers’ websites also linked abortion to causing long-term mental health issues, future infertility, and even breast cancer, associations not supported by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“Who doesn’t want to help a pregnant person? Of course we all would. My question is: is this the best, most effective way?” said Swartzendruber. Overall, she says, the results of PRCs are murky at best. “If we really want to help children or to help pregnant people, there are so many demonstrated, effective ways to do so.”

Kimport echoes this concern. “There is a broad absence of actual stories of people who have abortions,” she says. “Without their stories and without recognizing the ability and agency of the pregnant person to make a decision, there will be constant misunderstanding.”

Fear and stigma complicate the conversation, Kimport adds. “There is a huge fear of sharing one’s story around abortion. For people, organizations, or institutions who are interested in understanding, they need to establish themselves as a truly nonjudgmental listener.” She notes that threatening or violent language in these discussions can further block openness, limiting honest dialogue and the development of effective, evidence-based support.

For Amy Ford, despite navigating the obstacles of this complex system, her story eventually found a happy ending. The pastor, Brent Batson of Church of the Springs in Texas, who once condemned her pregnancy made a public apology during a church service 16 years later, calling his refusal to marry them the worst mistake of his ministry.

As he apologized, he turned to her son, Jess, and asked, “Will you forgive me for planting seeds of rejection in your heart before you were ever even born?” When Jess accepted, they hugged, and the congregation erupted in applause.

“A lot of my early ministry had to do with fault finding rather than helping people,” Batson said. He added that many Christians are taught to pursue purity and holiness by calling out perceived sin in others without considering the fallout. “In the Bible, who did Jesus have a problem with? Not people who were struggling with life and making bad choices. He struggled with the people who were throwing rocks at them.”

Batson now emphasizes a unified message within his church that celebrates compassion and understanding rather than judgment.

“The message should impact culture, and culture impacts behavior,” he said.

Today, Amy Ford leads Embrace Grace, one of the nation’s largest Christian nonprofit networks that connects pregnant women with local churches to provide mentorship and community support throughout pregnancy and early parenting.

Embrace Grace partners with Pregnancy Resource Centers, providing “love boxes” for clients that include a “best gift ever” onesie, a journal encouraging bravery and resilience, a book of 20 personal stories from women who carried their pregnancies to term, and an invitation to join a local Embrace Grace support group. These groups aim to equip and encourage women to feel capable of parenting, with a particular emphasis on building community support. Ford describes a national network that helps women secure employment, manage finances, and access essential resources, sometimes even providing major assistance like buying them a car.

“Every life has value,” said Ford. “True feminism and girl power is that you actually can have your baby and your dreams too. We say all the time that we want to make abortion unthinkable, so that a girl’s like, ‘Why would I need to have an abortion when there’s so much support out there?’”

While Ford’s optimism reflects the hope of what could be, Brittani Anthony’s experience reveals how distant that reality still feels. During her years of sidewalk ministry, she recalls that most churches she contacted declined to serve as points of contact for single mothers, despite identifying as pro-life. Many are content to donate to pregnancy resource centers, she said, but stop short of confronting the wider realities shaping women’s decisions, including economic insecurity, limited healthcare access, social isolation, and the stigma that still surrounds unplanned pregnancy.

The shift that is needed, Anthony believes, may require a decoupling of American Christianity from a strictly conservative political lens. It means supporting state and federal policies that advance the well-being of mothers and children, creating a culture where women are not shamed amid their circumstances, and addressing structural inequities that affect families from every background.

“It’s social, it’s political, it’s spiritual… it’s everything,” Anthony told More to Her Story.